Queer Lives at the Tower: The LGBT+ Stories that were almost on the tours

Date: 07 February 2020

Author: Matthew Storey

Queer Lives at the Tower, our new LGBT+ tours at the Tower of London are just a couple of weeks away, and the team are rehearsing to deliver a bold and new experience. Come, and you’ll see fascinating stories from the Tower’s past. However, there are some stories that didn’t quite make the cut. I’m going to tell you them here, to see what they tell us about how we work with LGBT+ history.

John/Eleanor Rykener (recorded in 1394)

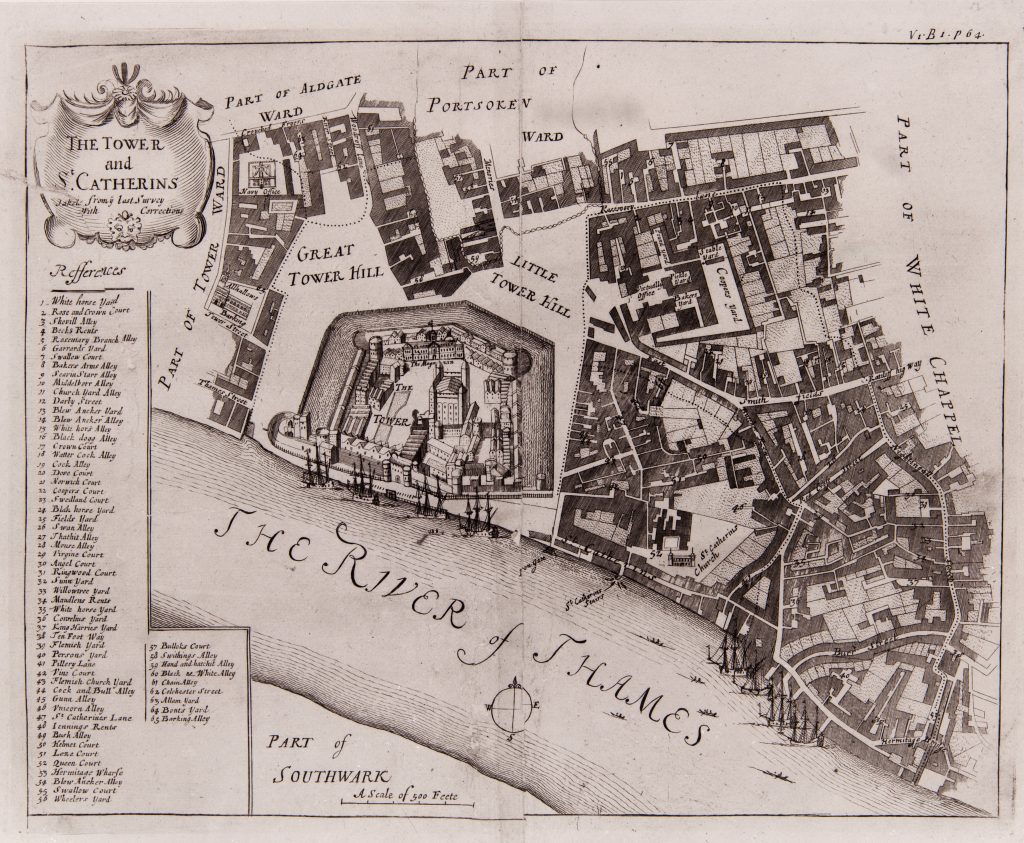

John/Eleanor Rykener was arrested on the night of 11 December 1394, only half a mile from the Tower. For a while they seemed a great candidate for our tours. We wanted the tours to represent a broad range of LGBT+ experience, and we wanted to tell medieval stories at the Tower. It is often hard to find sources of LGBT+ stories of ordinary people, and criminal records are one of the best places to start. The record of Rykener’s arrest in the Plea and Memoranda Rolls in the Corporation of London record office tells a remarkable story.

Rykener and a man called John Britby were caught having sex (‘committing that detestable, unmentionable and ignominious vice’ in the language of the time). Rykener, named as John in the record, had agreed to have sex only if Britby paid them for their work. Rykener was wearing women’s clothes, and the record says Britby approached them ‘as he would a woman’. Rykener was happy to give more details of their life, revealed that they had been taught to dress in women’s clothes and to be paid for sex by two women. Rykener had spent 1394 in Oxfordshire and Buckinghamshire living as a woman, known by the name Eleanor, and worked as an embroider, a tapster in an inn, and as a sex worker. Rykener revealed they had sex with men, including knights and priests, for money. They also had sex ‘as a man’ with women, including nuns, and did not do this for money.

While Rykener was unlucky to get caught, they openly shared their story, suggesting that many other people who lived a non-binary gender identity had a place in medieval society. Rykener lived and worked near the Tower. They were even paid for sex in the lanes behind the church of St. Katherine’s by the Tower. In the end, we decided that we wanted all our stories to be about people who we could connect directly to the Tower, and as far as we know Rykener never stepped inside. Reluctantly we had to leave John/Eleanor outside the walls.

Instead of John/Eleanor, we found another story from 1918 to show the history of trans lives at the Tower, one that we have never told before.

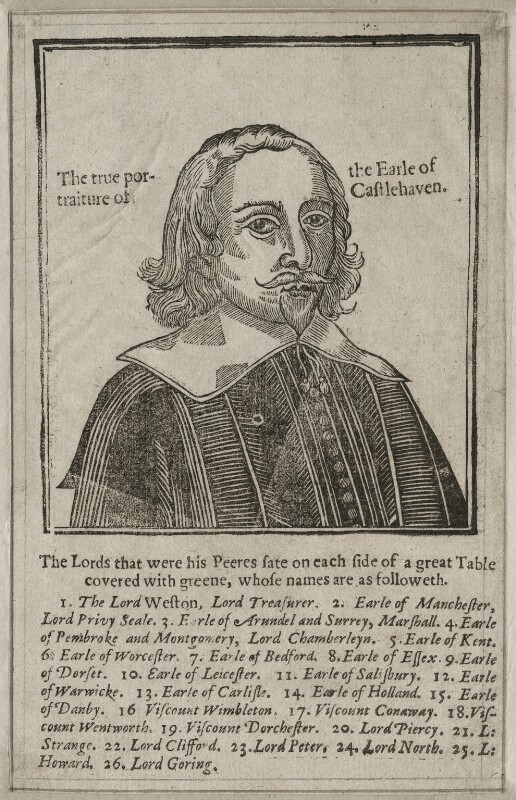

Mervyn Touchet, 2nd Earl of Castlehaven (1593 – 1631)

On 14 May 1631, Mervyn Touchet, 2nd Earl of Castlehaven, was led to the scaffold on Tower Hill, and executed for sodomy. He was beheaded and buried in the chapel of the Tower the same day. So far, so good, for inclusion in the Tower’s LGBT+ history. However, Castlehaven’s story is much darker and more complicated. He had also been convicted of rape. LGBT+ history is like any other history, and can show humanity at its worst, as well as its best.

Castlehaven’s household was dominated by a culture of abuse and exploitation. His own son, Lord Audley, had brought the complaint against his father to Charles I, and the trial by the Privy Council found ‘crimes too horrid for a Christian man to mention’. Castlehaven was accused of having sex with two of his male servants, and of raping his wife. The trial revealed a household in which Castlehaven had given power to two male favourites, Henry Skipwith and Giles Broadway. They had then been encouraged to abuse other members of the household, including Castlehaven’s young daughter-in-law. The trial was widely followed and was even reported on as far away as the English colonies in Massachusetts Bay.

Castlehaven’s story shows us that sexual relationships between masters and male servants existed in the early 17th Century. At the time the case was understood as the moral failure of Castlehaven as head of his household, and it also established a precedent for wives to testify against their husbands. In later years it began to be seen more and more as a story about homosexuality. Ultimately, we decided to focus on other stories for the Tower tours, as fully exploring Castlehaven’s trial, and doing justice to the experience of his victims, would have taken a lot of time.

We needed space for other fascinating histories, so instead we have focussed on other stories of same-sex desire.

Two Women

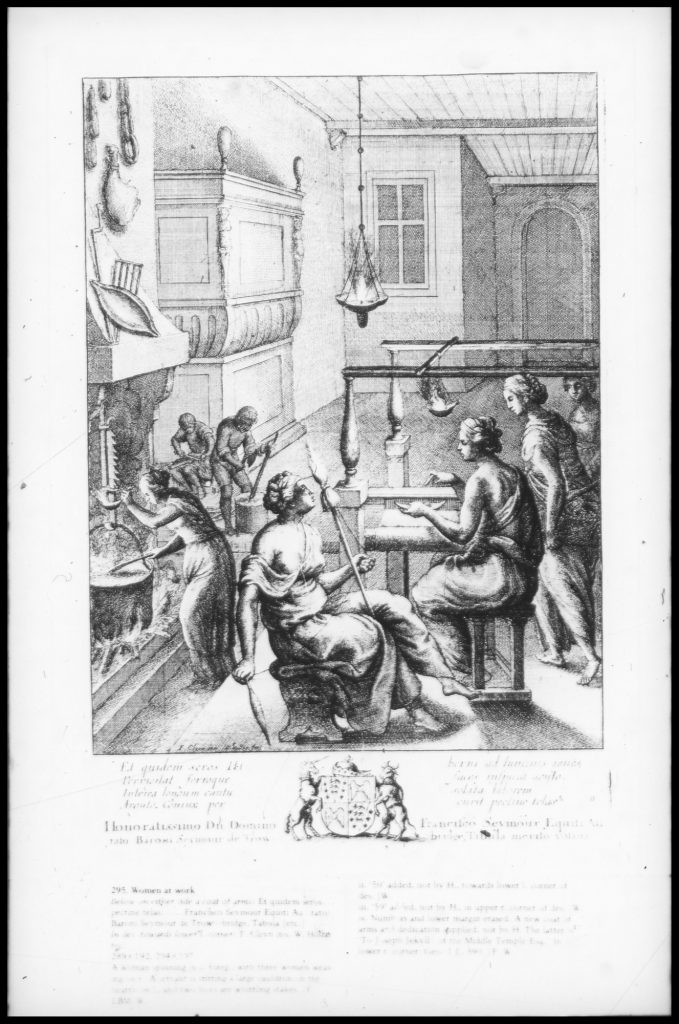

We spent a lot of time discussing the representation of same-sex love and desire between women in the Tower tours. Women’s stories can be particularly hard to find in medieval and early modern LGBT+ history. Unlike men they seldom appear in legal records, and fewer women could write to leave us their own account. As a military base, the Tower has left more traces of the men who have lived, worked or visited here, than the women. The most frustrating thing was that all the histories I found of women who loved and desired other women featured people who never set foot in the Tower!

Historians can take a piece of evidence that survives, and conjecture that it shows a common experience. We debated including two fictionalised women. The tours are structured as a play and allow for dramatic licence. Our fictionalised women could have been based on real stories of love and desire between women from the historical record. We could have looked to evidence from elsewhere in Europe, where sex between women was criminalised and so can be found in historical records. In 1477 in the German town of Speyer, for example, Katherina Hetzeldorfer was prosecuted for having sex with many women. One had been her lover for two years. In Amsterdam in 1750 two women were reported ‘for living as if they were a man and wife’ by their landlady. Closer to home we could have taken inspiration from Mary Hamilton, convicted of fraud in 1746 for dressing in men’s clothes and marrying a woman. When it was common to share beds, many cases of physical intimacy between women could have just gone unnoticed and unrecorded.

After a lot of discussion, we decided that all the stories we tell on the tours should be about real people with a definite connection to the palaces. We will have some fascinating stories of women coming up on the next tours at Hampton Court Palace and Kensington Palace.

Matthew Storey,

Curator (Collections)

More from our blog

Frances Stuart and Barbara Villiers

10 February 2023

Learn about the relationship between Frances Stuart and Barbara Villiers, two of the most influential women at the court of King Charles II.

The Real Norman Hartnell: Beyond 'Silver and Gold'

25 February 2022

February is LGBT+ History Month in the UK, which aims to increase the visibility of lesbian, gay, bisexual and trans (LGBT+) people through the exploration of their history and stories. Collections Curator Matthew Storey looks at one such story.

A Queer Walk through Hampton Court Palace

11 February 2021

When you next visit Hampton Court, bring a queer eye to the palace. Shift your perception. Actively look around you. I promise there is a rich history to find.