George III: The Mind Behind the Myth exhibition highlights

Date: 14 May 2021

Author: Polly Putnam

No one is defined just by their symptoms, yet George III is really only ever known as 'The Mad King'. In popular culture he is almost always portrayed as a buffoon. Not only is this portrayal not true, but it reflects much of society’s prejudice against people who suffer from mental illness. Like George in plays, books and musicals, real people with mental health issues are often ridiculed and dehumanised.

In the George III, The Mind Behind the Myth exhibition, we explore George III’s treatment for his ‘madness’ which took place at Kew, in 1789, 1801 and 1804. We have also included objects which tell us something of his passion and interests, and in so doing we have tried to show something of the real person as well as the ‘madness’. Here are some highlights.

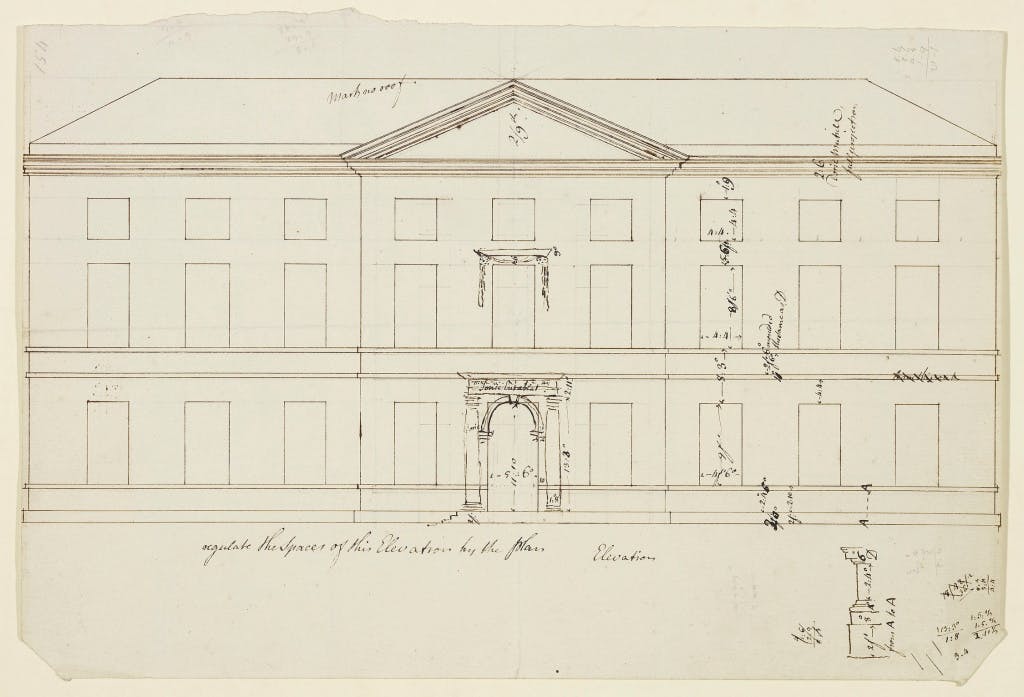

Annotated drawing by George III and William Chambers, c1758

This is one of my favourite objects in the exhibition. It is very possible that George III and his teacher, the architect William Chambers, worked together in Kew Palace on this drawing which was created before George III was king.

William Chambers was employed to teach George III architecture three mornings a week. He also designed ornamental buildings which peppered the royal gardens at Kew, including the Great Pagoda. Architecture was an enduring passion of George III's. He paid close attention to building projects and was known to sketch plans for buildings even when he was ill.

A 'repeating watch', 1802-03

The novelist William Thackeray said that George III was “testy at the idea of all innovations and suspicious of all innovators”. George III was actually fascinated by science and technology, and a generous patron of the sciences. He commissioned William Chambers to build him an Observatory in Richmond in 1768, where he kept a collection of scientific instruments and gave the astronomers, Caroline and William Herschel, generous pensions and £4000 for him to build a giant telescope. With it, they discovered the planet Uranus and the existence of galaxies.

His approach to his estates was also scientific: he experimented with crop rotations and varying breeds of livestock and crops and submitted his findings anonymously to agricultural journals.

George III had a soft spot for clocks and watches. He was fascinated by their technology and would often take them apart and put them together. He bought the latest models with all the bells and whistles; the watch we have on display is known as a 'repeating watch', which chimes every 15 minutes. George III worked long hours and expected the same of others. When he sent letters to politicians, he would note down the precise time it was written as well as the date. The watch tells us not only of his interests but also hints of something of the pressure he put himself under.

Capriccio View of the Piazzetta with the Horses of San Marco c1743-4

George III took his collecting seriously because of the realisation that he was collecting on behalf of the country as well as for the monarchy. Perhaps the single most important purchase was the collection of the artists’ agent, John Consul Smith in 1765. As well as important works by Italian artists such as Ricci and Zuccherelli, it included many works by Cannaletto considered at the time and today as one of the most important painters of architectural landscapes.

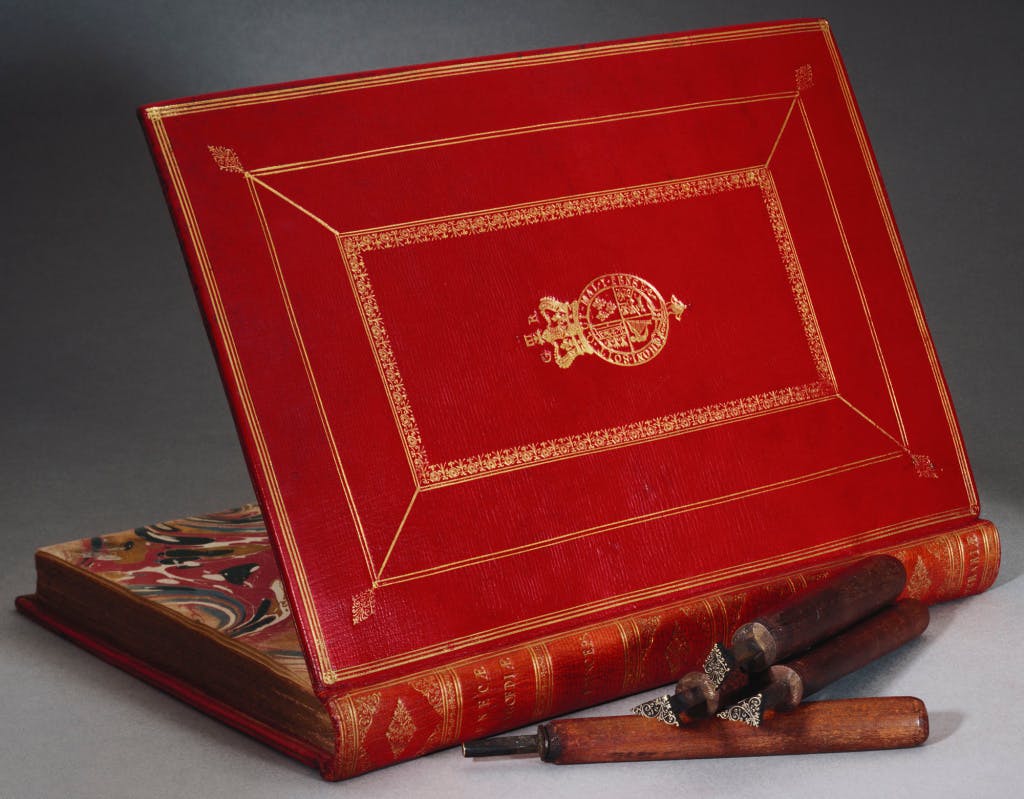

Book Binding tools

The purchase also included many rare books, which George actively collected and read. Each of his residences had a library, and he spent nearly £500o a year on books. Most of his collection of over 25,000 books was given to what would become the British Library in 1823. His collection was known not only for its rarity but also for its appearance: he founded a bindery at Windsor Castle, ensuring his books were bound in the finest and most decorative of leathers.

Transverse flute c1760

Perhaps George’s greatest passion was for music. He could play the organ, harpsichord, and flute, arranged for personal visits from famous musicians such as Mozart and Haydn if he found out that they were in the country, and organised and attended musical concerts. In the early years of their marriage, he and Charlotte would duet together on the flute and harpsichord. During his isolation for his illnesses he would play the flute, which he found consoling.

Accounts of the King’s Treatment, 1789

One of the greatest myths surrounding the 'madness' of George III is that he was miraculously 'cured' of it in 1789. It is true that he recovered enough to return to his duties as King. However, a small note by one of George's doctors — written the same day it was declared that there had been a 'complete cessation of his illness' — tells a different story:

February 26th 1789.

'Before he went to bed he was very low and cried — He mentioned to me the depression of his spirits.'

This reflects what for many people is a life-long struggle with mental health. George III was isolated at Kew again in 1801 and 1804 and stepped down from his duties and lived alone in Windsor from 1811 until his death in 1820.

George III's Waistcoat, c1820

This waistcoat was worn in the last days before his death at Windsor. It has been altered to accommodate his hunched appearance.

Included throughout the exhibition are testimonies of people who have had their own experiences with mental illness. We see these displays as a way of acknowledging, celebrating and welcoming everyone who has struggled with mental illness.

Polly Putnam

Collections Curator, Historic Royal Palaces

More from our blog

Lady Mary Wortley Montagu: Georgian Feminism, sexual-fluidity and disease

21 February 2020

To celebrate LGBT History Month, we are exploring some of the lives and loves of LGBT+ people at the palaces throughout history. This week we learn from Holly Marsden, Queer History placement student, about the life of one of Georgian society's most fascinating women: Lady Mary Wortley Montagu.

Celebrating Hillsborough Castle's Moss Walk

09 March 2020

Although moss gardens are a relatively common sight in Japan there are very few in the UK and Ireland. So it's special for us that one of the best examples in Northern Ireland is at Hillsborough Castle and Gardens! Gardens Manager Claire Woods introduces Hillsborough's Moss Walk.

The explosive history of the pagoda during World War II

06 June 2023

One of the most surprising periods in the history of the Great Pagoda is its use as a secret testing site during World War II. Curator Polly Putnam picks up the tale of this fascinating discovery.