Behind the scenes of Mind Behind the Myth with Daniel Regan

Date: 19 August 2021

Author: Daniel Regan

How does the story of George III's treatment at Kew Palace inform discussion of male mental health today?

For our exhibition Mind Behind the Myth, we partnered with local community groups to interpret some of the objects on display, reflecting on how what we know about George’s ill health speaks to mens’ lived experiences in 21st-century London. Over a series of sessions, the group found out more about George III’s story, explored their own mental health journeys, and contributed directly to the final exhibition with object labels offering personal and creative responses.

In this special blog, freelance photographic artist and group facilitator Daniel Regan reflects on his experience with the group, and shares photographs of the time they spent working together.

This blog post explores mental health, past and present, and could be difficult for some readers. If you require mental health support please contact your local GP and/or organisations such as Maytree, CALM (men), Mind, Papyrus or Young Minds (young people).

Image: Photographic artist, facilitator and producer Daniel Regan © Daniel Regan

I discovered photography as a young person, coinciding with the onset of my own mental health difficulties. I had never been seen as ‘good’ at art at school, which mostly consisted of drawing bowls of fruit and quite frankly misbehaving. Discovering photography became a way of making art on my own terms, transporting myself into a different world whilst also entering into the beginnings of processing my difficulties. With photography I did not have to talk about how I felt. I could simply make images. Those images could be ambiguous and open to interpretation by those around me, meaning that I could safely explore complex feelings but without being left feeling vulnerable. Later on, the images became catalysts for conversations with my mother about my mental health.

In those early years I had no idea that art and mental health would become so intrinsically linked for me, both personally and professionally. Yet both have led me on a colourful – and sometimes challenging – rollercoaster in life. I now work as a professional photographic artist primarily focusing on both personal and commissioned projects relating to mental health and wellbeing. I also run my own non-profit organisation, the Arts & Health Hub. We support artists working in the arts and health sector by offering both professional and affective support. A number of those artists are like me with lived experience of mental health difficulties. For 5 years I also worked as the Director of a pioneering arts and health charity embedded into primary care in the NHS in north London.

I often work on socially engaged projects that encourage community groups to use the arts to explore their own mental health. When I was approached to work on this project at Kew Palace I was intrigued, but admittedly had reservations. As someone of mixed Caribbean heritage I have my own qualms with the lack of acknowledgement of the history of colonialism within the heritage sector, although I have seen increased efforts recently. As someone from a working-class background with minimal engagement with heritage sites as a child (besides the odd school trip), heritage has not often felt culturally accessible to me either. This project was an opportunity for me to engage in both heritage and mental health in a way that felt entirely appropriate to me.

When I learnt that my role would be focused on engaging a group of men with lived experience of mental health difficulties with George III’s historic objects my interest was piqued. I had lots of questions about the intentions of the project: what did HRP hope to achieve? How was the wellbeing of the men being considered? When lived experience becomes a focal point for community projects my initial thoughts are about the emotional labour that participants go through reliving often difficult memories and experiences. It is our duty to consider how to support people in this type of work, so that the emphasis is not on the tangible outputs of a project, but on elevating and respecting their voices. In my 15 years of working on participatory projects it is the first time I have seen the voices of community groups elevated alongside the voice of curators in such a prestigious venue such as Kew Palace.

HRP worked with a number of local community organisations that already support men with mental health difficulties through various groups: MIND in Richmond, The Dalgarno Trust and SMART London. Potential participants were initially invited to an introductory visit to Kew Palace to find out more about the project, including meeting myself. It was an opportunity to clearly hear about the aims of the project and how they would be achieved. Through a number of sessions the men would be able to discover more about the history of Kew Palace and the life of George III. Most men were aware of the familiar trope of George as the “Mad King” and were interested to know more about his life. They clearly understood that whilst one of the aims was to contribute their own text labels to the exhibition in relation to historic objects, there was also the opportunity to dive deeper into George’s history and their own experiences through creative writing, conversations and trips to other heritage sites.

Around 8-10 men joined the project. In our initial session I felt it was important to share some of my own lived experience with the men. Often when working with community groups I find it useful to share my story to help build a connection. I spoke about my own experiences of being in hospital and my project Abandoned. After my own first hospitalisation I spent a number of years photographing abandoned mental asylums, contemplating on my own experiences and the differing ways in which we have treated patients in the past. It helped for the men to see that I am not an outsider, but someone who also lives with difficulties.

The group were also treated to an intimate learning discussion from HRP Curators Polly Putnam and Matthew Storey, hearing about the history of Kew and George III’s life. They were able to openly ask questions about George’s mental health and familiarise themselves with the palace and its grounds, where there were no judgements about their knowledge of history or heritage. It was a safe space to learn and build knowledge about this fascinating king and the multiple facets to his identity. At this stage we were introduced to the catalogue of objects that would be featured in the upcoming exhibition. From flutes and pocket watches to paintings and medical documents, the men instantly became curious about the objects and attracted to different types. I, myself, was mostly interested in letters regarding George from his doctors. It made me think a lot about my dual roles both as patient and also when I have worked in healthcare — the idea of how we are seen and how we see others.

Creative writing can be quite an intimidating activity for anyone. But through a series of different creative tasks, the men went on journeys through time, their own lives and George’s life to reflect on mental health past and present. They wrote prose and poetry about objects that resonated with them; letters to a younger George from an older version of himself; and curatorial labels that represent the contemporary man today. Objects — both ours and others’ — can hold so much emotion. They tell not only our own stories but spark stories in our imaginations that could once have belonged to others.

In these sessions we learnt so much about each other through the writing exercises, followed by reflections and sharing. We learnt about different monarchies and cultural histories through group participant Roberto’s choice of George III’s finishing crown, part of his collection of book binding tools. Being from Portugal meant that Roberto had a different perspective on monarchies and we learnt that one of the bullets that struck Pope John Paul II in 1981 was later encased in the crown of the image of Our Lady of Fatima.

For another participant the paintings of gardens and landscapes by Johan Jacob Schalch deeply resonated with them. After a period of illness, their own garden became a source of solace, no doubt as Kew Gardens did for George himself:

“Some things haven’t changed throughout history. Creating a garden is a slow, often very personal process of trial and error and a constant work in progress – much like life itself. Perhaps George found peace and solace in the healing and recuperative qualities of the natural environment, as many do today.”

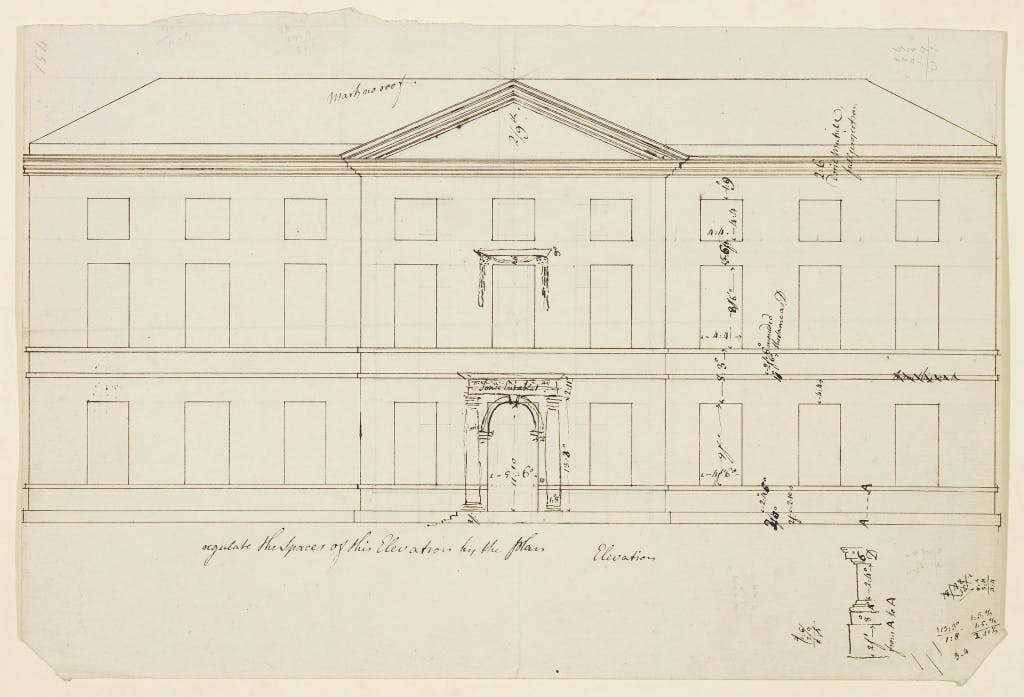

Anderson, an artist himself, particularly benefited from knowing about the architecture of Kew Palace and the buildings across the gardens, which influenced some of his own drawings. On a special trip to Windsor Castle the men were able to see a number of personal art pieces that belonged to and were by George. We were taken on a private tour by the librarians, including meeting some of the conservators who taught us about how objects such as shoes, dresses and blazers are restored. Anderson was inspired by a number of architectural drawings on show, leading him to write this poem:

“By day, pillars of stone

By night, columns of

shade

Circling dome

Upstanding mound

Folly alone

Standing its ground

Eight or twelve pillars

Two or four steps

Dividing each cycle

Seasons windswept

Demarking boundaries

Royally kept

Beginning with exercise

Strengthening eyes

Tensioning limbs

Perfecting lines

Ending with follies

Marbling surrounds

A monarch restrained

His creations abound”

In one of the most moving sessions I tasked the men (myself included) to bring in an object that holds significant importance to their mental health. By bringing in our own objects and reflecting on their meaning we were able to deeper identify with the items being exhibited. For some it was a watch that held significance after a breakdown, for others it was an object that has travelled with them through the years. For myself, it was a large set of keys that belonged to my late mother, which remind me to stay curious to the magic of the world.

Alongside the curatorial labels that the men contributed to the exhibition, a number of people (including myself) loaned objects of significance to Kew Palace, now on display on the top floor. By far the most emotionally moving part of the exhibition, these objects on show (and a short film) offer real life modern day stories by people affected by mental health difficulties. It’s a poignant way to bring the history of George’s mental health into context with contemporary voices of lived experience. As I walked around the exhibition for the first time I was moved to tears by the vulnerability that others were sharing with the public. To see my own mother’s keys on show, a few years after her death, reminded me of the magic of our complex relationship and how important her role was in supporting me to understand and embrace my own mental health. I believe that this exhibition, which blends past and present together, is a fantastic opportunity to reflect on mental health in relation to where we have been, where are are now, and where we would like to be.

If you’re experiencing mental distress and need support then I have found these particular organisations to be doing great work:

- CALM (Campaign Against Living Miserably) focus on supporting men at risk of suicide (75% of all suicides are males).

- Maytree provide fantastic befriending support for those in suicidal crisis.

- Both Papyrus and Young Minds offer mental health support for young people.

Daniel Regan

www.danielregan.photography

More from our blog

George III: The Mind Behind the Myth exhibition highlights

14 May 2021

In the George III, The Mind Behind the Myth exhibition, we explore George III’s treatment for his ‘madness’ which took place at Kew, in 1789, 1801 and 1804. We have also included objects which tell us something of his passion and interests, and in so doing we have tried to show something of the real person as well as the ‘madness’.

Lady Mary Wortley Montagu: Georgian Feminism, sexual-fluidity and disease

21 February 2020

To celebrate LGBT History Month, we are exploring some of the lives and loves of LGBT+ people at the palaces throughout history. This week we learn from Holly Marsden, Queer History placement student, about the life of one of Georgian society's most fascinating women: Lady Mary Wortley Montagu.

The explosive history of the pagoda during World War II

06 June 2023

One of the most surprising periods in the history of the Great Pagoda is its use as a secret testing site during World War II. Curator Polly Putnam picks up the tale of this fascinating discovery.